A new kind of CAR-T becomes a micro-pharmacy, eliminating glioblastoma in mice

n immunotherapy for cancer, the buzziest area of research is combinations: one checkpoint drug with another, say, or a checkpoint drug with chemotherapy. The latest brainstorm is an acronym lover’s dream team: CAR-Ts and BiTEs.

In a mouse study reported on Monday in Nature Biotechnology, the one-two punch vanquished glioblastoma, the incurable brain cancer that killed Sen. John McCain last August. You may be wondering:

What is this dynamic duo?

CAR-Ts are immune cells that are genetically engineered to produce a receptor that docks with a molecule on cancer cells. The two that have been approved, Novartis’s (NVS) Kymriah and Gilead’s (GILD) Yescarta, both in 2017 and both for blood cancers, dock with CD19.

Feverish research is underway to make CAR-Ts work against solid tumors, but so far none really do. A BiTE (Amgen (AMGN) has trademarked the acronym), or bi-specific T-cell engager, is a lab-made antibody with two molecular hooks: One grabs a T cell and the other grabs to a tumor cell. That creates a molecular bridge that stimulates the T cell to produce tumor-cell-killing proteins.

How were CAR-Ts and BiTEs combined?

Scientists led by Dr. Marcela Maus of Massachusetts General Hospital started by creating CAR-Ts. Theirs, however, targeted not CD19, as Kymriah and Yescarta do, but a different molecule on tumor cells called EGFRvIII (the last part means “variant three”). It’s especially prevalent on glioblastoma cells.

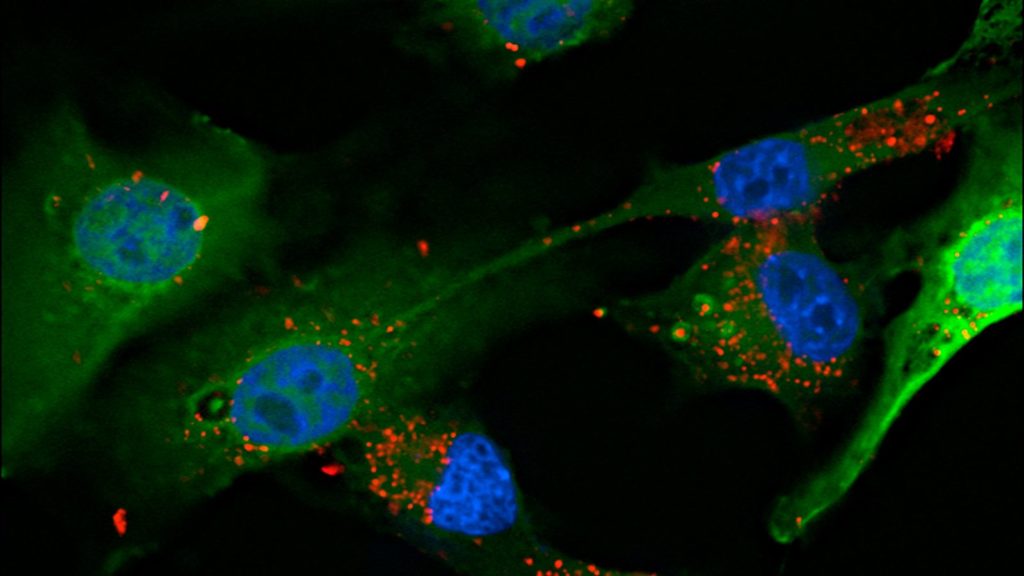

Here’s where it got clever: The scientists then introduced a second gene into T cells, this one for a BiTE. One end of the BiTE’s antibody bridge grabs the EGFR on tumor cells and the other grabs CD3 molecules on T cells. The CD3 end activates T cells to flood the zone with tumor-killing molecules. (EGFR is on brain tumor cells but not healthy brain cells.) In other words, Maus turned CAR-T cells into micro-pharmacies stocked with anti-cancer compounds.

How did it go?

When they gave the CAR-Ts to mice with human glioblastomas grafted into their brains, after three weeks more than 80% of the animals showed a “complete response,” Maus said, meaning there was no evidence of any tumor.

Why might this approach be better than CAR-Ts alone or BiTEs alone?

BiTEs are too big to get across the blood-brain barrier. Also, they don’t last long and therefore have to be given as a continuous infusion — 28 days for Amgen’s Blincyto (blinatumomab), a BiTE approved for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. T cells have no problem crossing into the brain. “Having the CAR-T produce the BiTE gets the BiTE into the brain and produces them continuously,” Maus said. “That could provide a substantial advantage.”

How optimistic should we be, since … mice?

True, the vast majority of therapies that cure cancer in mice fail in people and never make it into clinical use. Still, the mouse results are similar to those with the two approved CAR-T therapies, so there’s that. Also, glioblastoma has such a terrible survival rate, anything that helps even a few people would be very welcome. Just over 10,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with glioblastoma every year; the median survival is about 15 months.

What do scientists not involved in the new study think?

BiTE expert Dr. Farhad Ravandi of MD Anderson Cancer Center cautioned that the approach is “highly experimental” and the results are only in mice, but said “it could potentially be very interesting and very effective.” However, while engineering CAR-Ts to produce BiTEs offers continuous tumor-killing after a single infusion, he said, if a patient experiences toxic effects from the BiTEs (not uncommon with Blincyto), there’s no way to stop the CAR-Ts from churning them out.

Immunotherapy expert Dr. Renier Brentjens of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center called the research “scientifically sound and very creative,” adding that “CAR-T cells are a technology that is very much in its infancy and has a very high ceiling.” Maus’s invention, he added, could be less toxic and more effective than CAR-Ts or BiTES alone.

This must be the kind of innovative research the National Institutes of Health loves, right?

Most of Maus’s funding came from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation and Stand Up to Cancer. She was repeatedly denied NIH funding. Some grant reviewers didn’t consider her proposed CAR-T/BiTE research a high enough priority; others said she was using the wrong kind of mice. She stuck to her guns, used the mice she thought right, and got the success she’s now reporting.

What’s next?

Maus and Mass General have applied for a patent on the CAR-T/BiTE invention, and she is trying to raise $3 million to make medical-grade CAR-Ts (that requires a special, expensive vector to carry the desired genes into the T cells). She’s also trying to gin up industry interest in a clinical trial. “With glioblastoma, there is hesitation from industry because there have been so many failed therapies,” she said. “But we’re trying, because we think this has a real shot.”

Brentjens agrees: “I have no doubt the Food and Drug Administration would approve a clinical trial” of the technique.

Leave a Reply